n <- 800

C <- rnorm(n)

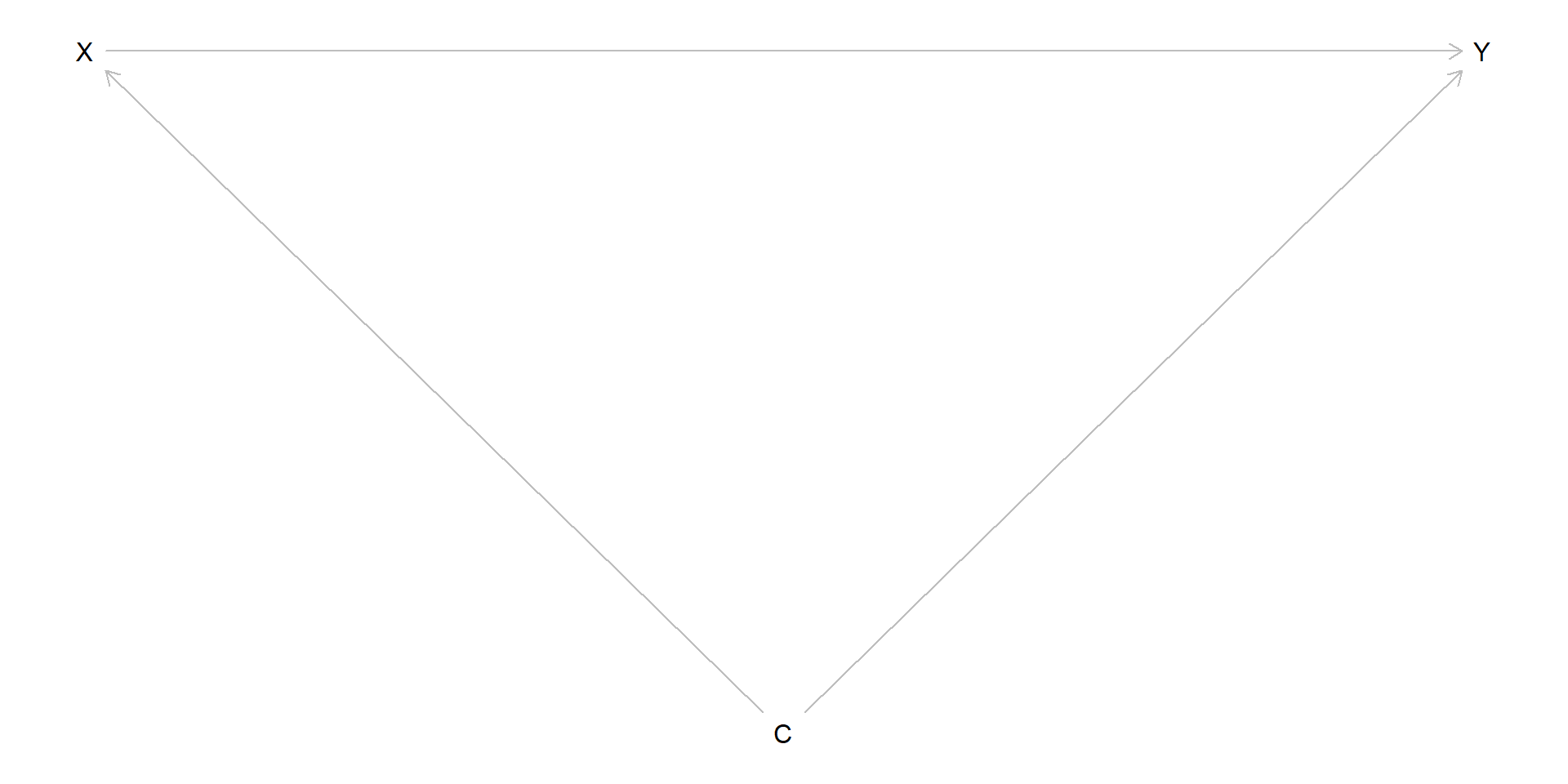

X <- rbinom(n, 1, plogis(-1 + 2 * C))

Y <- 1 + 1 * X + C + .5 * X * C + rnorm(n)

simdata <- data.frame(C, Y, X)

e.mod <- glm(X ~ C, data = simdata, family = binomial)

e.hat <- predict(e.mod, type = "response")

simdata$W <- simdata$X / e.hat + (1 - simdata$X) / (1 - e.hat)

with(simdata, mean(X * Y * W - (1 - X) * Y * W))[1] 1.092786