Improving the speed of computing causal bounds

@gjo11

Source:vignettes/vertexenum-speed.Rmd

vertexenum-speed.Rmd

library(causaloptim)

#> Loading required package: igraph

#>

#> Attaching package: 'igraph'

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

#>

#> decompose, spectrum

#> The following object is masked from 'package:base':

#>

#> unionWhat is causaloptim?

In summary, causaloptim computes symbolic tight

bounds on causal effects. Suppose we have a causal graph

in which we want to estimate an effect

.

If there is unmeasured confounding of this effect, then it cannot be

determined. However, we can still try to find good bounds on it!

Let’s pretend for a while that the confounding was in fact measured, so we have an estimate of its distribution . Then, given , the effect is identifiable. Now, even though we don’t actually know , we surely know something about it; it needs to be consistent with the structure of , so it satisfies some constraint, say . With no further assumptions, is valid w.r.t. if and only if we have , so finding tight bounds on becomes a constrained optimization problem; simply find the extrema of .

For a given estimate of the distribution

of our measured variables, we could try a large number of

simulations and numerically approximate the bounds, but can we actually

solve the problem analytically to get closed form expressions of the

bounds in terms of

?

For a certain class of problems, it turns out we can! This is precisely

what causaloptim does, and this post will highlight some of

its inner workings and recent efficiency improvements. For a tutorial on

how to get started using causaloptim, have a look at this

post.

Background

Back in 1995, [Balke & Pearl]1 showed how to do this in a classic example of an experiment with potential non-compliance. More on that shortly, but in summary they showed how to translate their causal problem into a linear programming one and leverage tools from linear optimization to compute the bounds. Balke even wrote a command line program in C++ that computes them, given such a linear program (LP) as input. His program has been used successfully by researchers in causal inference since then, but has had a few issues preventing it from wider adoption among applied researchers.

causaloptim was written to solve these problems. It can

handle the generalized class of problems defined in [Sachs & Jonzon

& Gabriel & Sjölander]2. It removes the burden of translating the

causal problem into an LP and has an intuitive graphical user interface

that guides the user through specifying their DAG and causal query. It

has until version 0.7.1 used Balke’s code for the

optimization. However, for non-trivial instances of the generalized

class that causaloptim handles, the original optimization

algorithm has not been up to the task.

Efficiency matters!

Let’s time the following simple enough looking multiple instrument problem.

Benchmark Example. Multiple Instruments.

library(causaloptim)

library(igraph)

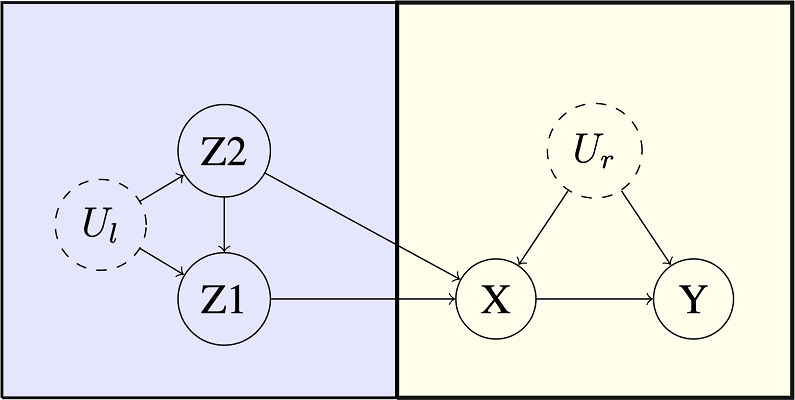

b <- graph_from_literal(Z1 -+ X, Z2 -+ X, Z2 -+ Z1, Ul -+ Z1, Ul -+ Z2, X -+ Y, Ur -+ X, Ur -+ Y)

V(b)$leftside <- c(1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0)

V(b)$latent <- c(0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1)

V(b)$nvals <- c(2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2)

E(b)$rlconnect <- c(0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)

E(b)$edge.monotone <- c(0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)

obj <- analyze_graph(b, constraints = NULL, effectt = "p{Y(X = 1) = 1} - p{Y(X = 0) = 1}")Using causaloptim version 0.7.1 to bound

we got (with a 3.3 GHz Quad-Core Intel Core i5; your mileage may

vary)

system.time(oldbnds <- optimize_effect(obj))

#> user system elapsed

#> 31093.57 47.02 61368.22Note the times (in seconds)! 😱 Our CPU spent almost

hours working on this! 🤖 And we spent more than

hours waiting! 😴 Correctness is not enough; having to wait until the

next day is a bad user experience. Using causaloptim

version 0.8.0 however, we get

system.time(newbnds <- optimize_effect_2(obj))

#> user system elapsed

#> 0.139 0.001 0.140Now this is acceptable! 😊 Of course, we need to verify that the results are the same. It is difficult to see upon visual inspection that they are the same, because the vertices are returned in a different order (and there are lots of them). Instead we can randomly generate some probability distributions that satisfy the graph, and compute the bounds and compare the results. First, we create the R functions that compute the bounds:

eval_newbnds <- interpret_bounds(newbnds$bounds, obj$parameters)

eval_oldbnds <- interpret_bounds(oldbnds$bounds, obj$parameters)Then, we create a distribution by first randomly generating the

counterfactual probabilities, and then calculating the observable

probabilities by using the constraints implied by the DAG (which live in

the constraints element of obj).

sim.qs <- rbeta(length(obj$variables), .05, 1)

sim.qs <- sim.qs / sum(sim.qs)

names(sim.qs) <- obj$variables

inenv <- new.env()

for(j in 1:length(sim.qs)) {

assign(names(sim.qs)[j], sim.qs[j], inenv)

}

res <- lapply(as.list(obj$constraints[-1]), function(x){

x1 <- strsplit(x, " = ")[[1]]

x0 <- paste(x1[1], " = ", x1[2])

eval(parse(text = x0), envir = inenv)

})

params <- lapply(obj$parameters, function(x) get(x, envir = inenv))

names(params) <- obj$parametersThen we pass the probabilities to the bounds functions and compare:

do.call(eval_newbnds, params)

#> lower upper

#> q0_0 -0.3148649 -0.08804175

do.call(eval_oldbnds, params)

#> lower upper

#> q0_0 -0.3148649 -0.08804175Success!

This improvement was achieved by modernizing a key back-end

optimization algorithm and implementation. To see how it fits into the

bigger picture, let’s first see how causaloptim sets up the

optimization problem.

How does causaloptim work?

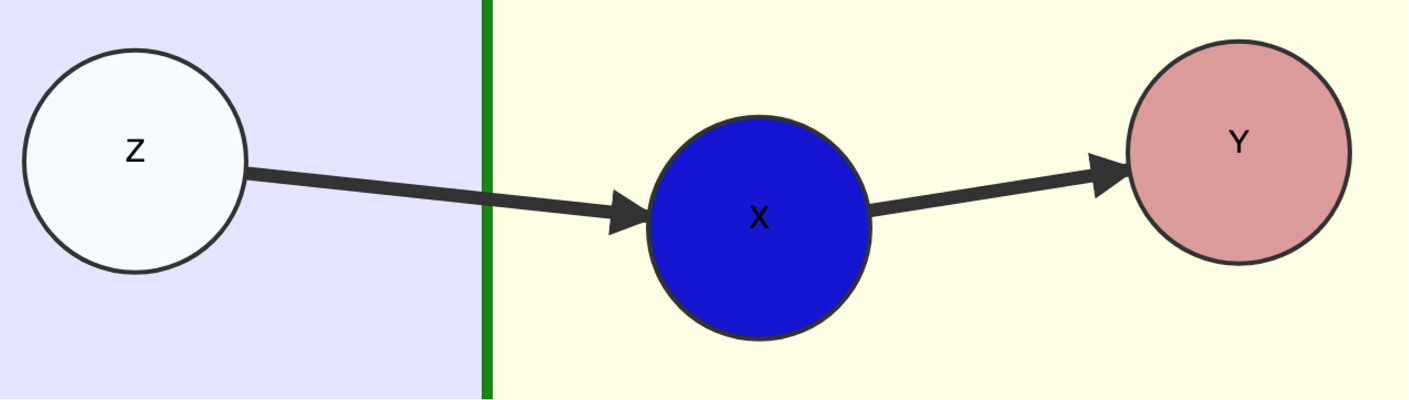

Given a DAG , causally relating a set of measured binary variables, suppose we can bipart so that all association between the two parts is causal and directed from one part (which we call ) to the other (called ), and we want to determine the effect of some variable on a variable . As a guiding example, let’s follow along the original one given by Balke & Pearl.

Original Example: User Input DAG .

Since we assume nothing apart from the macro-structure

,

we must augment

with a “worst case” scenario of confounding among each variable

within the parts

and

to get a causal graph

.

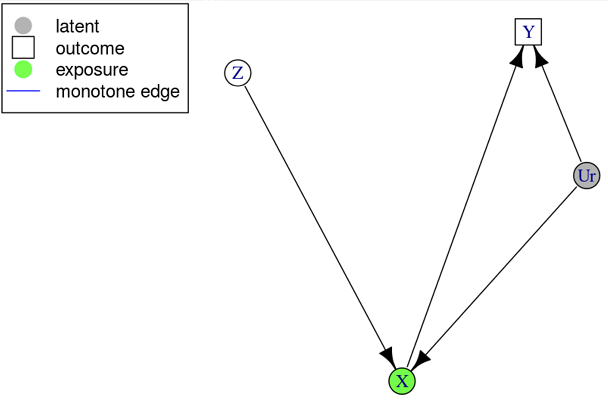

The specific causal graph below can be interpreted as an experiment with

potential non-compliance. We have three binary measured variables;

treatment assigned

,

treatment taken

and outcome

.

We want to estimate

,

which is confounded by the unmeasured

and has a single instrument

.

Original Example: Causal Graph .

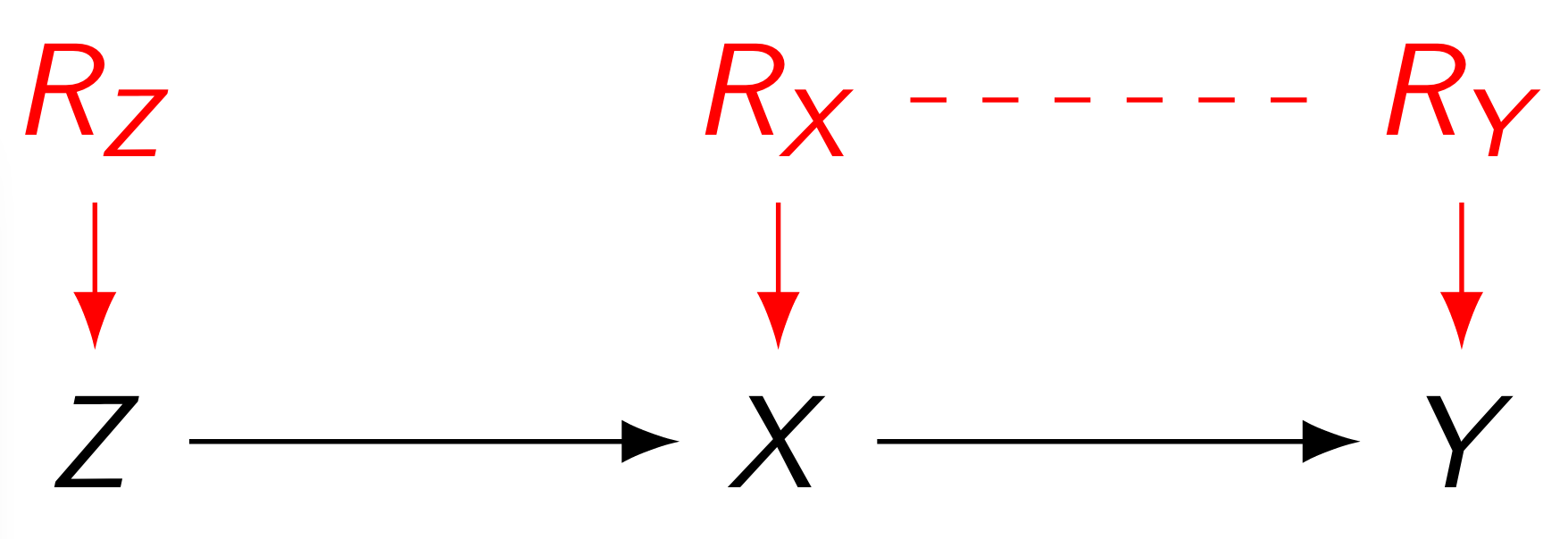

Response Function Variables

This yields a functional causal model , although not in a computationally convenient form. However, by the assumption of finite-valued measured variables , we can in fact partition the ranges of the unmeasured ones into finitely many sets; they simply enumerate the finitely many distinct functions for each . We call such a canonical partition of the response function variable of .

Original Example: Response Function Variables.

(The dashed line signifies $R_X\not\!\perp\!\!\!\perp R_Y$.) In the context of our specific example, where e.g. has a single parent only so takes exactly distinct values, say where , we have

Parameters and their Relationships

We can observe the outcomes of the variables in , so we can estimate their joint distribution, but in fact we will only need their conditional distribution given , so let’s establish some notation for this. For our specific example we define Although unknown, we need notation for the distribution of the response function variables as well. Our specific example requires only By the Markovian property, our example yields Note that all coefficients are deterministic binary, since e.g. , and by recursion the same applies to more complex examples. Thus, in our particular example, we have Further, we can express potential outcomes of under intervention on in terms of the parameters by the adjustment formula; Hence, we have

Linear Programming

Now we have our constraints on

as well as our effect of interest in terms of

and we are ready to optimize! By adding the probabilistic constraints on

we have arrived at e.g. the following LP giving a tight lower bound on

:

By the Strong Duality

Theorem3 of convex optimization, the optimal value

of this primal problem equals that of its dual. Furthermore, its

constraint space is a convex polytope and by the Fundamental Theorem

of Linear Programming4, this optimum is attained at one of its

vertices. Consequently, we have

Since we allow the user to

provide additional linear inequality constraints (e.g. it may be quite

reasonable to assume the proportion of “defiers” in the study population

of our example to be quite low), the actual primal and dual LP’s look

slightly more complicated, but this small example still captures the

essentials.

In general, with

,

and user provided matrix inequality

,

we have

The coefficient matrix and right hand side vector of the dual polytope

are constructed in the few lines of code below (where

).

Vertex Enumeration

The last step of vertex enumeration has previously been the major

computational bottleneck in causaloptim. It has now been

replaced by cddlib5, which has an implementation of the

Double Description Method (dd). Any convex polytope can be dually

described as either an intersection of half-planes (which is the form we

get our dual constraint space in) or as a minimal set of

vertices of which it is the convex hull (which is the form we

want it in) and the dd algorithm efficiently converts between

these two descriptions. cddlib also uses exact rational

arithmetic, so we don’t have to worry about any numerical instability

issues, e.g. Also, it already interfaces with R6. The following lines

of code extract the vertices of the dual polytope and store them as rows

of a matrix.

library(rcdd)

hrep <- makeH(a1 = a1, b1 = b1)

vrep <- scdd(input = hrep)

matrix_of_vrep <- vrep$output

indices_of_vertices <- matrix_of_vrep[ , 1] == 0 & matrix_of_vrep[ , 2] == 1

vertices <- matrix_of_vrep[indices_of_vertices, -c(1, 2), drop = FALSE]The rest is simply a matter of plugging them into the dual objective

function, evaluating the expression and presenting the results!

The first part of this is done by the following line of code, where the

utility function evaluate_objective pretty much does what

you expect it to do (here

(c1_num,p)

separates the dual objective gradient into its numeric and symbolic

parts).

expressions <- apply(vertices, 1, function(y) evaluate_objective(c1_num = c1_num, p = p, y = y))There are still a few places in causaloptim that are

worthwhile to optimize, but with this major one resolved we looking

forward to researchers taking advantage of the generalized class of

problems that it can handle!

Happy bounding!